SLURPING 001

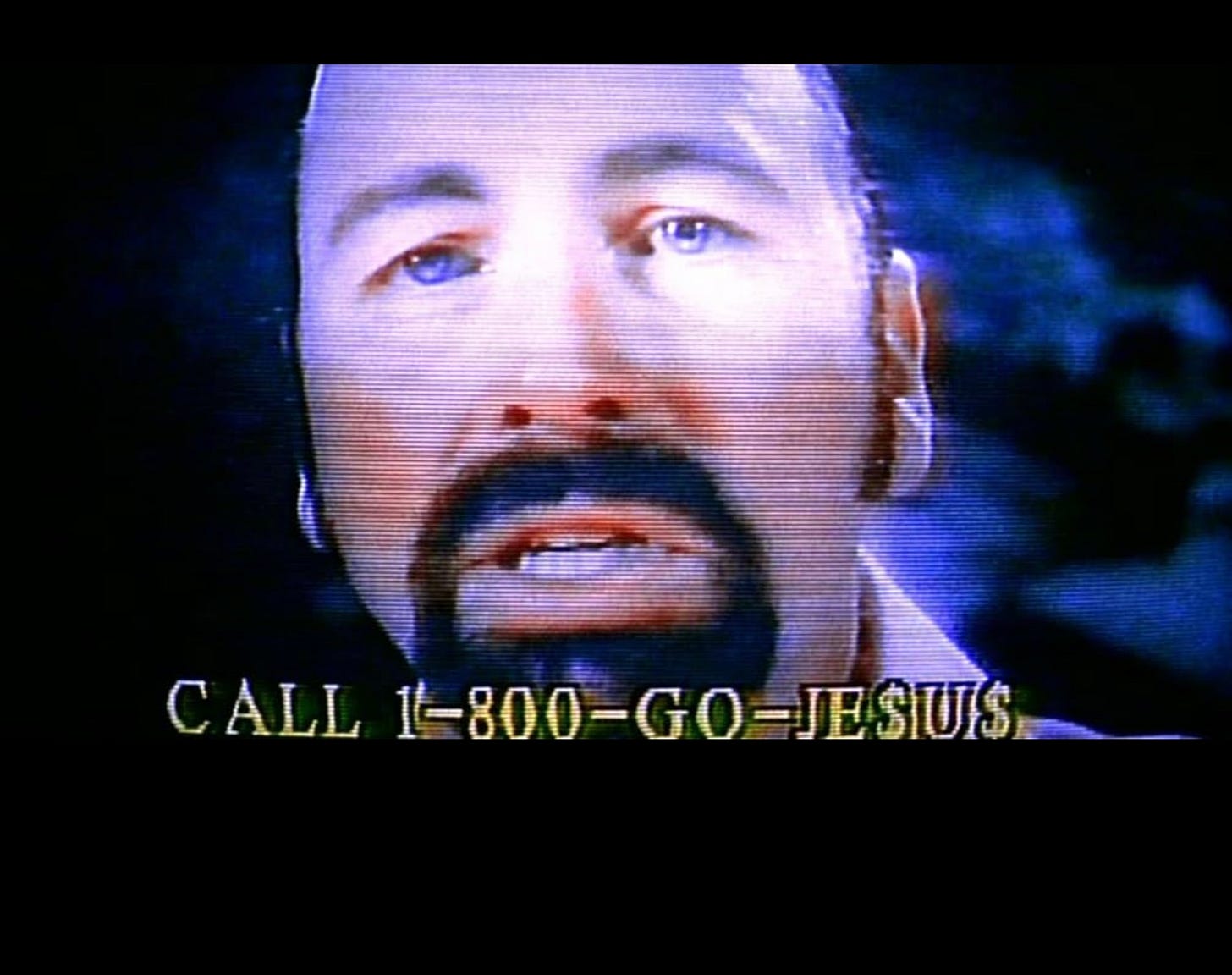

Call 1-800-GO-JE$U$

Hi first slurp very exciting stuff! Really this is just a stylish way to share my interests and recommendations and sometimes goings-on of the moment with friends etc who would like to know.

sip:

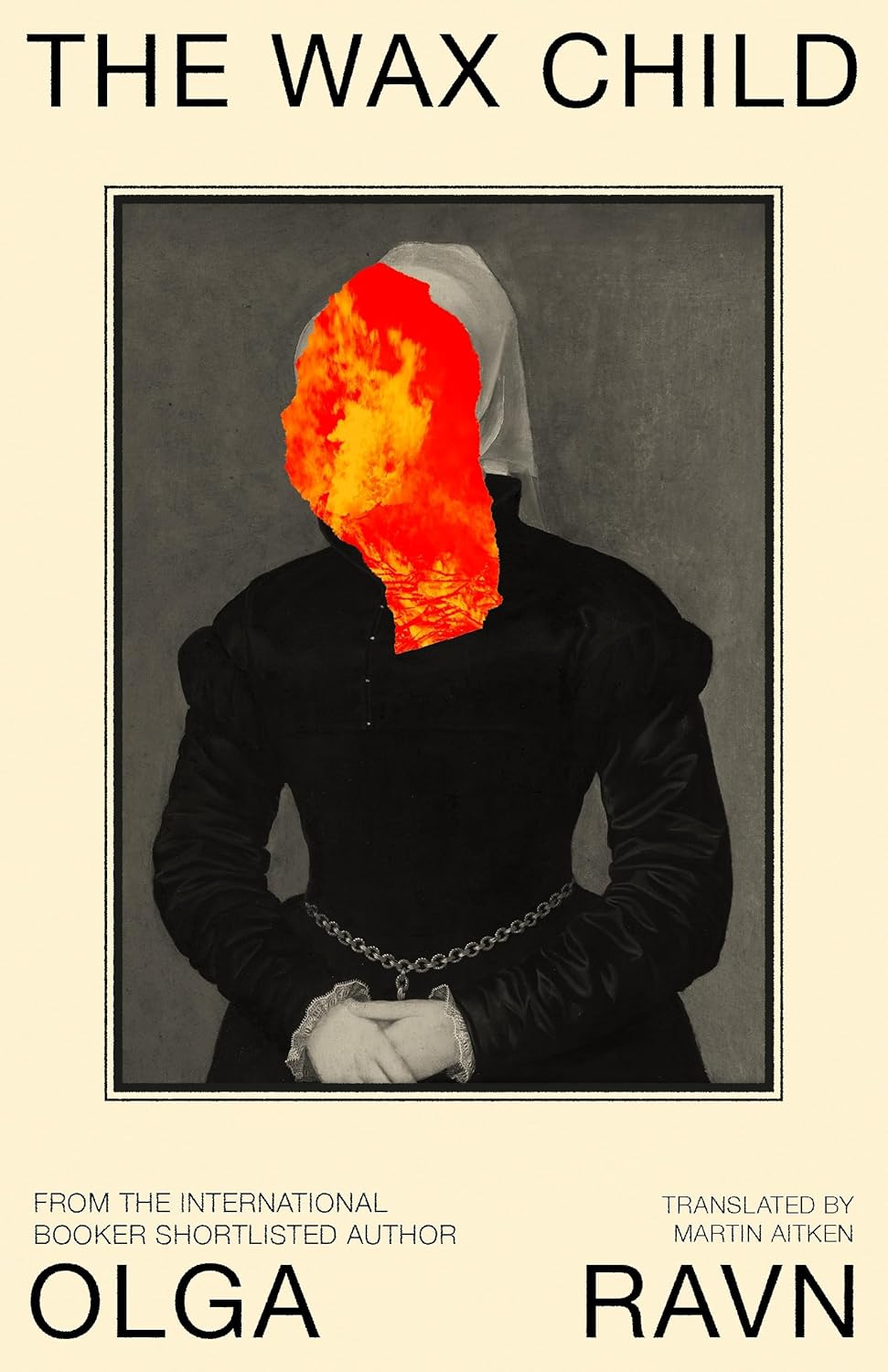

Favorite recent read is The Wax Child, based on a 17th century danish witch trial, which came out last month. Perfect fall read it is Evoking fr. The Culture has been saturated with witch trial stuff as of the last ten years or so.. and still, I do love. Honestly, specifically, I love a European witch trial (shout out to Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch, which I read years ago and still think about). This book has the added delight of being narrated by a baby made out of wax and fingernails and hair and stuff. I absolutely adore a weird little guy. Also, just, Olga Ravns beautiful mind. Nobody is writing like her. It’s like less than 200 pages and I found myself bookmarking multiple places because her prose is so weird and cool and interesting and I WILL be returning to it. I absolutely loved The Employees when it came out a few years ago and this didn’t disappoint. So tasty. You can read a snippet published by Kismet.

Slurp:

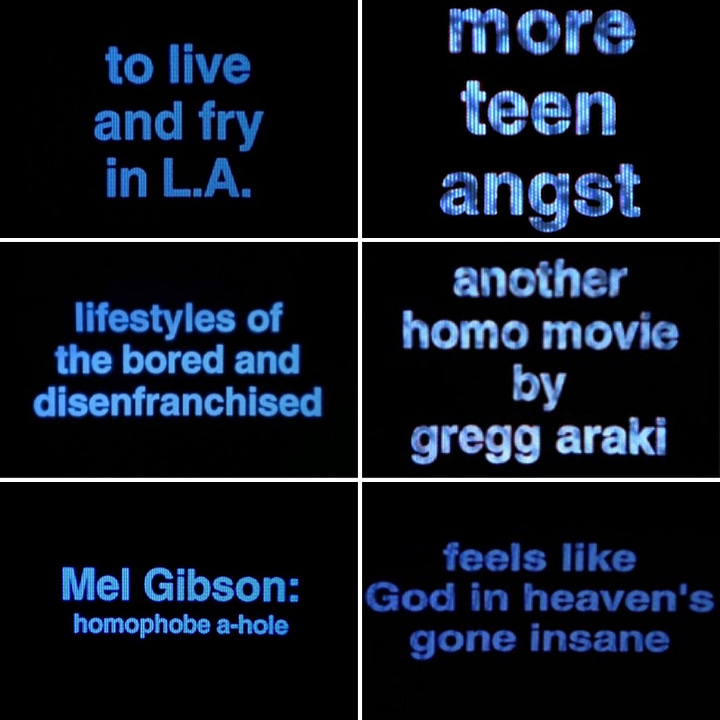

Time to wax poetic.. my big big rec for this email is Gregg Araki’s most beautiful and brilliant Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy — Totally F**ked Up (1993), The Doom Generation (1995), and Nowhere (1997). Much to say.

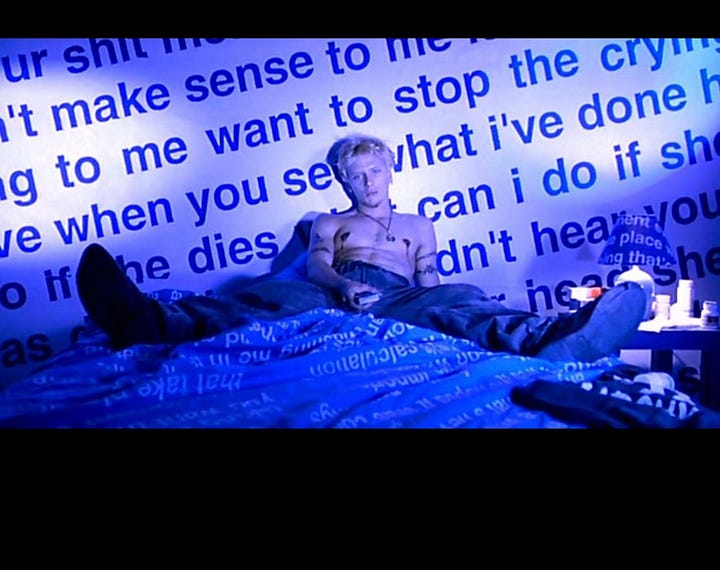

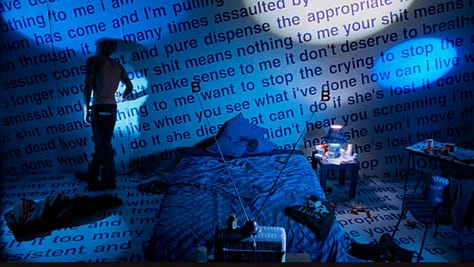

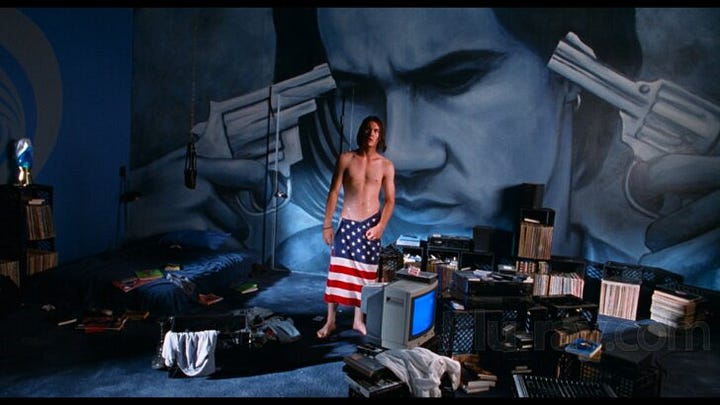

These are some of the most stylish movies ever made. Not just because they’re chic, but because Araki’s work is so aesthetically distinct. Glowing lights in liquor stores, starless night skies, desolate drive-ins where teenagers go to fuck, get fucked up, and/or fuck each other up. There’s a coffee shop in Bushwick that I’ve often described as “like if there was a gas station that sold kratom in Twin Peaks” (shout out Caffeine Underground, the coffee is terrible and there’s nothing quite like it) and these movies feel sort of like that. Except very good. Even with the non-budget ($25k) allotted to Totally F**cked Up, Araki conjures a distinct mood that is carried through and heightened in the following films. The glowing text-filled screens that dot TFU reincarnate in a teenage drug addict’s bedroom in Nowhere.

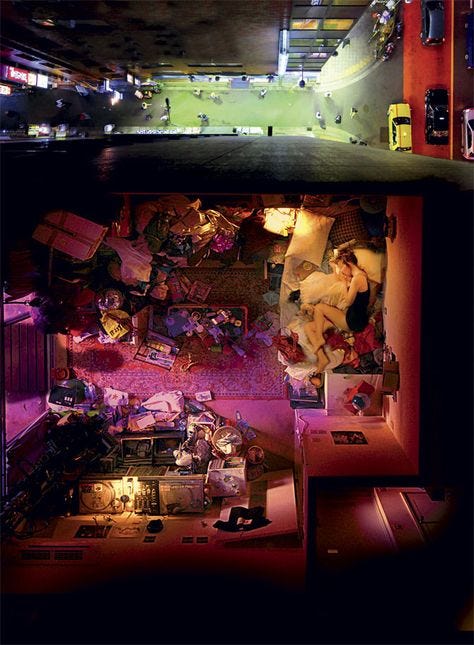

Which brings me to: THE SETS! This is where the increase in budget across the films is really notable. Bedrooms really stand out in each installment, and the execution in Nowhere is genuinely incredible. As only teenage bedrooms can truly be, each room is a direct expression of its inhabitant: their desires, perceptions, beliefs, sense (or curation) of self.

Araki shoots LA to perfection, which is to say it’s sprawling and sort of miserable but also erotic and magnetic. Big blank concrete walls, gay romance in empty parking garages, aqua blue swimming pools, suicide and murder amid suburban domesticity, awkward fucking in cars.

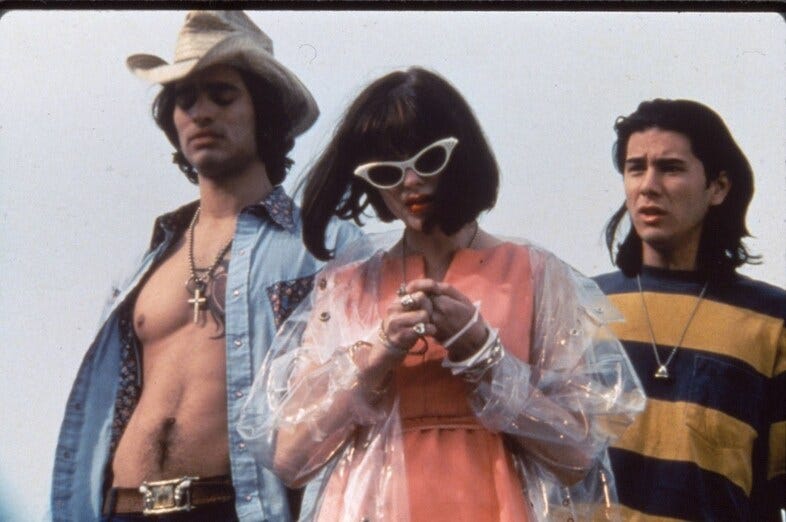

The Doom Generation is my least favorite of the trilogy (it’s the darkest of the three and missing some of the camaraderie of friendship that makes the other two films particularly special IMO) but it undoubtedly has the best wardrobe and Rose McGowan is a fucking sight in each and every outfit. While TDG had a much bigger budget ($750k) than its predecessor, the wardrobe that makes it so iconic was mostly thrifted and borrowed from the costumer’s friends and lovers. This movie would probably have given me nightmares in high school but I definitely would’ve done everything in my power to copy her look.

These movies are gruesome. They’re also funny and touching and I have been thinking about them for days. The undercurrent of the ongoing fallout of the AIDS crisis is the real heart of what makes them work. A lizard alien thing with a laser gun sporadically picking off characters in an otherwise not-about-aliens movie works surprisingly well as a metaphor.

What interests me is that these movies feel so current despite the fact that the threat of AIDS no longer has the same hold on queer culture and lives that it did thirty years ago. Most gay teenagers today probably don’t remember a world before the existence of PrEP. And still, when Dark, the protagonist of Nowhere played by Duval, records a diary entry toward the end of the film, I can relate

Dear diary, what a day. I swear I’ve never been so depressed, miserable, and lonely in my entire life. It’s like I know there’s got to be somebody out there somewhere... just one person in this huge, horrible, unhappy universe who can hold me in their arms and tell me everything is going to be okay. And how long do I have to wait before that person shows up. I feel like I’m sinking deeper and deeper into quicksand... watching everyone around me die a slow, agonizing, death. It’s like we all know way down in our souls that our generation is going to witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes. It’s in mine, look. I’m doomed. I’m only 18 years-old and I’m totally doomed.

It’s hard to find anyone in my generation (Z) that feels particularly optimistic about what the future holds, myself included. Maybe it was a relief to watch a movie that feels like it agrees that we can hardly blame them. Of course, Araki isn’t only pulling inspiration from the AIDS crisis—he criticizes capitalism, consumer-friendly religion, the cult of celebrity, and the instant, if fleeting, relief of sex and drugs. He expresses anxiety over general pointlessness, climate change, addiction, attacks on the gay community, the desire for real connection. Most of these issues have stuck around or mutated over the last thirty years. Some of them have grown worse.

In an essay for Criterion, Nathan Lee summed it up pretty well:

For several years, in a queer-cinema course I teach to university students, I have prefaced screenings of Nowhere with a content warning to end all content warnings: this movie features violence, substance abuse, eating disorders, rape, suicide, everything, you name it. And while over time more and more students have opted out of watching it, those with a stomach for the tough stuff have found the movie oddly consoling and even cathartic. Young people today are, after all, grappling with their own generation’s apocalyptic conditions: mass shootings, climate disaster, surging authoritarianism, the profound disruption of their formative years wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, and attacks on reproductive autonomy and LGBTQ rights. For all the ways it maps a quintessentially nineties psychosocial terrain, the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy will resonate as long as teenagers feel lost, restless, angry, and powerless—which is to say forever. Nowhere might well have been called Now, Here.

Lately I’ve been thinking about whether you can have hope without optimism. Hope is something I strive to maintain even on the worst days, whether it’s hope about the direction of my own life, or about political change, or just choosing to believe that small things matter (whatever that means). Politically, I fully believe that hope is the most important ingredient for successful leftism. Without hope, we don’t do things like volunteer our time (or, yes, go to the polls for Zohran), or generally engage with the world at all. Maybe stubbornly grasping at hope is its own kind of optimism, even if I usually feel like things are falling apart and maybe think that they really are. Then again, I’m told every generation feels that it will be the one to watch the world end. The narcissism of the human condition, etc.

I would argue that we have more ways to end the world, or at least life as we know it (knew it?), right now than at any other point in history. I would also argue we haven’t enough done to mitigate that. It’s hard to have those feelings so firmly rooted inside of you and not go full doomer.

Suicide is a recurring motif throughout the Teenage Apocalypse movies. After all, whats the point of sticking around if everything really is doomed, if real love either doesn’t exist or is so fleeting that your beloved may be revealed to be a meat incubator for a giant alien cockroach mere moments after you find each other in this huge, horrible, unhappy universe?

It’s been on my mind lately (not in a concerning way, relax) particularly after reading the brilliant essay “The Limits of My Language: Meditations on Depression” by Eva Meijer, that it is actually pretty easy to feel like there’s no real point in sticking around. There have certainly been times in my life where the knowledge that I have the ability to “opt out” came as a small (fucked up) comfort. Meijer argues that we have to make reasons for sticking around for ourselves, and I think that’s true. Most days I resign myself to the belief that things can get better, even if I don’t really think that they will.

Still, I must have some lingering traces of hope, maybe even optimism, left in me. When I watched the Teenage Apocalypse movies the feeling that overwhelmed me (as is often the case when I watch a really great movie for the first time) was delight that there is so many things in the world that I will someday love and haven’t encountered yet. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Nowhere was both the final installment in the trilogy and the most moving for me personally. This piece with Jourdain Searles points out

Though “Nowhere” is by far the most bizarre installment of the trilogy, it’s also the one that most represents Araki’s point of view. He says the trilogy is meant to “hold the promise of a chosen family.” Despite all the darkness of his work, he wants to give queer audiences light: “There is a world for you out there. Maybe you don’t see it right now, maybe you’re living in some shithole town in Missouri, but there is a whole world out there. The trilogy opens the door to that world. It’s here. You just have to get through your shitty teenage years, graduate, go to college, and find it…”

You can watch the Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy on the Criterion Channel rn or elsewhere on the internet I’m sure.. Worth it imo haha

Xox Cloe

Ps the soundtracks deserve their own essay! Magnificent.